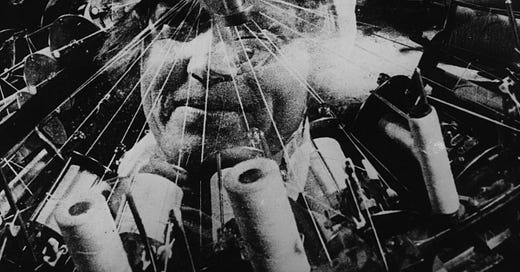

Vertov sets things in motion with an ambitious claim — a warning, even — that Man with a Movie Camera won’t be like anything you have ever seen or heard. The film is an experiment, an absolute “separation from the language of theatre and literature,” according to the film itself. In cinema, Vertov saw the potential for something truer, something more real than the other arts. He conceived of cinema as a microscope for society, the fusion of science with the newsreel. Cinema was the “organization of real life,” (Vertov 38), not the dramatization of emotion and adventure. He saw this inclination toward the dramatic as a screen, a distraction from reality, and in dropping intertitles and eschewing methods of other artforms, he succeeds in bringing cinema — and its viewers — closer to that reality.

However, I somewhat disagree with Vertov. This singular method doesn’t bring us closer to reality, or at least not closer to our material surroundings. The uncut take certainly does: a single shot of a tree waving in the wind is the truest, most unaffected reproduction of reality cinema can muster. Rather, compared to other artforms and other modes of filmmaking, Vertov’s take on cinema better reflects the structure of thought, how the the brain truly functions. By dropping the pen, the drama, the story structure and so on, and in utilizing only the camera and the edit as tools, film is able to cascade over the waves of human thought, to float atop the sea of cultural consciousness. Drama and imposed emotional cues act as filters, impeding and jumbling the flow of consciousness.

In 1929, Man with a Movie Camera was likely in a world all its own. In fact, I argue that it still is today. The film achieves something special; it evokes a certain nebulous connection that goes beyond the reality of 1920s Russia. It holds up nearly a century later because Vertov and the the Council of Three hit upon a more dynamic expression of time and space. (The "Council of Three" was Vertov, his wife/editor Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother/cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman. They penned manifestoes in LEF, a radical Russian magazine.) Like sculptors, Vertov and Svilova shape the clay of time into a dynamic, moving work, which affects precisely in how it mirrors the flow of thought. Its lasting power lies in its form, so familiar because it reflects how we think, not — in the case of Eisenstein’s work — what we thought.

Consider the segment where the woman wakes, a parallel to the Russian cities rising in the morning. The woman washes her face and arms. The city’s lampposts and trash cans receive their morning spray. The woman dries her face. A cleaning woman wipes down a window. The links made between these shots are associative, in the same way our thoughts roll off one another in an unconscious stream, bobbing into consciousness, sometimes in a barrage of mental images, with seemingly tenuous links to our material surroundings. Had the filmmakers chosen to structure dramatically, like literature and plays, the film’s form would fold over a prescriptive, predetermined backbone, one likely defined by Aristotle millennia ago. Instead, no such filter stands between Svilova and the film. Film is a new, independent artform. Its flow is a stream of consciousness riding upon informed associations.

The filmmakers take the segment a step further. Next, after drying her face, the woman opens her eyes. Her window shutters open. A camera lens attempts to focus. The flowers outside come into focus. The shutters close and open as if they were blinking. The woman blinks. The shutters and woman alternately blink in rapid succession. The effect is dizzying. Then, linking the two images, the camera appears to blink, closing and opening its shutter. On a conscious level, this segment links a trinity of similar functions, nearly following a narrative: a woman blinks in order to focus; a camera focuses and also blinks its aperture; and the shutters — also a lens to the outside world — similarly “blink.” More, all three possess an unconscious, associative link in the editor’s mind, and the signifiers swirl: morning, focus, camera, blinking, aperture, shutter, shutters, etc. Again, rather than assembling the images according to a narrative structure, Svilova has ordered them associatively, the way our human mind grasps for connections. And later, like an echo, pulling the link again back to the woman and, deeper still, to Russia (and more, to the collective human consciousness), the filmmakers show us the movie poster, “The Awakening (of a Woman),” just as the cameraman walks past, camera in hand. The brain pulls together these associations, as does the editor, and this is why the film resonated then and still resonates today: our brains still function much the same.

In this way, Vertov succeeds in his aim. The film de-codes the world, organizes real life, opens our eyes and clears our vision by turning the camera lens (microscope/newsreel) on our consciousness. The film makes Russia live because its very form reflects the mechanics of thought in the Russian mind, in the human mind. And more, it exists still today because those mechanics of thought are universal. We see ourselves not just in the subjects on screen but in the shots the cameramen capture and the cuts the editor makes. There are no pretensions in this method because there are no filters in place to screen or organize the flow of observations into a prescribed form. The form is contingent on thought, and if the filmmakers’ particular ideas were tied to social productive forces in Russia at the time, the content reflects this. But, overall, their aim succeeds and the film lasts regardless of its time and place. Man with a Movie Camera is more than a reflection of social reality; it’s a microscope to the mind, a mirror to the collective unconscious, a documentation of the process of human thought, and this is why — seemingly ahead of its time — the film still fascinates us today, and likely will for as long as we have the means to view it.

Works

Vertov, Dziga. “On the Significance of Nonacted Cinema” Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov. Ed. Annette Michelson. Berkeley: U. of California P., 1984. Print.

Films I Watched This Week

I got a little back into the movie-watching groove this week, one step further from the warm, soothing comfort of holiday films and back into the COLD, UNFEELING GRASP OF REAL CINEMA. I should mention that when I bold a film, it means I really appreciate it.

I’m hoping to post my top films of 2020 by the end of the month. There are still so many films (released in the US in 2020) to see.

Rewind (2020) directed by Sasha Joseph Neulinger

Soul (2020) directed by Pete Docter

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) directed by Alain Resnais (rewatch)

Come to Daddy (2019) directed by Ant Timpson

The Woman Who Ran (2020) directed by Hong Sang-soo

About Endlessness (2019) directed by Roy Andersson